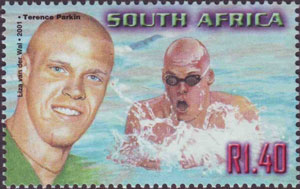

Living Loud: Terence Parkin - Olympic Swimmer

This article is part of our “Living Loud” series, which in addition to featuring well-known people who are deaf or hard of hearing, also highlights hearing individuals or unique developments that have positively impacted the world.

Terence Parkin, nicknamed the “Silent Torpedo,” has been called the Michael Phelps of the Deaflympics.1 He has competed for South Africa in Olympic and Deaflympic Games, World Cup and Pan American Competitions. Parkin is the Deaflympics’ most successful athlete since its inception in 1929, holding the record of the most medals — 34 in total. He has participated in 5 Deaflympics, in which he won 29 gold, 3 silver, and 1 bronze medals, plus South Africa won the bronze when he competed in the 2005 Deaflympics in Melbourne.2 He also earned an Olympic Medal for the 200m breaststroke in the 2000 Olympics in Sydney.3

Terence Parkin was born in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe on April 12, 1980. He was born deaf, but his parents, Neville and Bev didn’t realize he was deaf and it was not confirmed by doctors until he was 18 months old. His father Neville said, "We were both young when he was born and, being our first kid, we weren't really sure. His baby talk was normal, he laughed, he smiled — he was like a normal kid." There was a lack of educational options and support systems for deaf children in Zimbabwe at that time, so the Parkins decided to move to Durban, South Africa when Terence was three years old. Another literal bump in the road for Parkin occurred when he was in a car accident as a child. He persevered and his scar and shaved head became one of his trademarks in swimming competitions.6

He loved water and began swimming at age 12. He said, "I just love swimming, I enjoy it so much. I actually enjoy the feeling of getting tired from swimming.”6 But it was hard work and dedication that propelled Parkin to success. His coach, Graham Hill said, "I saw a kid who really wanted to get into swimming, but wasn't quite up to the standard of the other kids his age. He had more enthusiasm than the other kids. but just wasn't there. We used to laugh about it, we still do laugh about it. Terence was really slow when he came.”6

It was at the Midmar Mile held in South Africa, the world’s largest open-water swimming event, that he first made his mark. “Starting in the second batch of swimmers in the 13-and-under age group, behind all the seeds, he powered through the field, and when the times had been adjusted, he had taken a stunning victory. It was astounding, but Parkin has been doing astounding things all his life.”7

Parkin was dedicated to training and would spend hours everyday swimming, cycling, and running. He said, “Success is 90% attitude and 10% training….with the right attitude you can do anything. The worst disability is (bad) attitude!”1

Just getting warmed up.

In 1997, at age 17, Parkin competed in his first Deaflympics in Copenhagen, and won seven medals: five gold and two silver.

Parkin's 2000 Olympic Silver Medal for the 200m Breaststroke (Photo Credit: Terence Parkin / Graham Hill News Twitter)

In 2000, Parkin competed in his first Olympic games at the age of 20 in Sydney. He said "I am going to the Olympics to represent South Africa, but it's so vitally important for me to go, to show that the deaf can do anything. They can't hear, they can see everything. I would like to show the world that there's opportunities for the deaf.”5 He was the only deaf swimmer in the Games and claimed a silver medal in the 200m breaststroke.3 After he finished the race, unable to hear stadium commentators announcing the results, Parkin looked to the scoreboard, where he saw a “2” next to his name and thought that was just his lane number. He was ecstatic a few moments later when he realized the "2" meant he had gotten second place and won the Olympic silver medal.9

People often wonder how Parkin can hear the sound that signals the start of the race. The “signal” to start races has changed over time, from a gun being shot in the air, to a very loud buzzer, to a buzzer and a strobe light. Parkin watches for the strobe light, but before strobe lights were used, his coach would signal to him or use a light like a camera flash.6 In footage of Parkin’s races at the Sydney games, it appears the FINA referee holds his hand out, giving the visual signal for “set.”8

Terence tried to use hearing aids during a race once, but the crowd noise was distracting. "I can concentrate, I can focus on what I'm doing. I don't have to listen to the discussion or negative talk around me, so I'm able to focus. I don't have to worry about what other people say.”6 He hopes to inspire deaf athletes, as well as athletes from smaller countries, and show that with hard work you can be successful and you can win Olympic medals.4 5

In 2001, at the Rome Deaflympics, Parkin claimed five more golds – the 100m and 200m freestyle, the 100m and 200m breaststroke, and the 400m individual medley.

Parkin won the Midmar Mile in 2000 and 2002 — the world's largest open-water swimming event and the race where he first felt a taste of success when he participated in the 13-and-under age group.

And the medal count climbs.

At the 2005 Deaflympics in Melbourne, Parkin became the most successful competitor in the history of the Games, winning an incredible 12 gold medals and one silver.

In the freestyle, he won the 100m and 400m in the Games' record times and captured the 200m and 1500m with world records.

He won the 50m breaststroke with a world record time, and also claimed the 100m and 200m breaststroke titles.

To this he added the 200m butterfly, with another world record, as well as the 200m and 400m individual medley. Parkin was also part of another two world records, in the 4x100m medley relay and the 4x200m freestyle relay. His silver came in the 4x100m freestyle relay.

Additionally, his 13 medals helped South Africa to win bronze in the overall medal count at the 2005 Deaflympics, with a total of 19 metals.

At the 2009 Deaflympics in Taipei, Parkin was back on the winners' podium with 7 gold medals for the 50m, 100m, and 200m breaststroke, the 200m and 400m individual medley, and the 200m and 1500m freestyle.

Oh, and he also won a cycling bronze in the 93-kilometer road race! It wasn’t his first race; in 2005, he won gold at the World Deaf Cycling Championships in the 120km road race and picked up silver in the mountain bike event.

Legacy of a Champion

Parkin has become an icon. He has won over 400 gold medals, 200 silver medals, and 50 bronze medals through various competitions, and continues to hold Deaf World Records.1 He has participated in 2 Olympics, 5 Deaflympics, 2 Commonwealth Games, 1 Goodwill Games, FINA World Championships, FINA Swimming World Cups, Pan Pacific Championships, Africa Games, South Africa National Championships, and 24 Midmar Miles. He had a South African stamp issued in his honor in 2001. He has also been named an ambassador of the Princess Charlene of Monaco Foundation. He has received many awards including World Deaf Sportsman of the Year (1997, 2000, 2001, 2005), CISS Sportsman of the Century (2000), SA Schools Sportsman of the Year (2002), and Gold Presidential Awards (2000, 2001, 2002).1 Additionally, in 2011 Parkin saved a 7-year-old boy from drowning after he got his arm stuck in a swimming pool vent at a Johannesburg gym.10

Today Parkin lives in Johannesburg, South Africa with his wife and two children. He coaches sports at the St. Vincent School for the Deaf.11

Resources

Adapted from: Cartwright, B. & Bahleda, S. (2015). Did You Know? Terence Parkin, Swimmer. In Lessons and Activities in American Sign Language (p. 133). RID Press.

- Ambassadors & Advisors: Terence Parkin. Princess Charlene of Monaco Foundation. Retrieved 8/12/2016 from http://www.fondationprincessecharlene.mc/en/ambassadors-advisors/terence-parkin

- Terence Parkin. Deaflympics. Retrieved 8/12/2016 from http://deaflympics.com/athletes.asp?7679

- Terence Parkin. Olympics. Retrieved 8/12/2016 from https://www.olympic.org/terence-parkin

- Griffin, Stan. Olympic Silver to Deaf South African Swimmer. Deaf Friends International. Retrieved 8/12/2016 from http://www.workersforjesus.com/dfi/857.htm

- Terence Parkin. Wikipedia. Retrieved 8/12/2016 from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Terence_Parkin

- (2000, March 12). Terence Parkin - The silent success. SABC Carte Blanche. Retrieved 8/12/2016 from http://swimhistory.org/champions/1992/terence-parkin?start=1

- (2013, July 12). Parkin: Deaflympics legend continues South African. Retrieved 8/12/2016 from http://www.southafrica.info/news/sport/deaflympics-parkin-120713.htm#.V64Q7WXzQUU

- Flaherty, Bryan (2012, April 19). USA Swimming will allow hand signals to accommodate deaf athletes at Olympic trials. The Washington Post. Retrieved 8/12/2016 from https://www.washingtonpost.com/sports/usa-swimming-will-allow-hand-signals-to-accommodate-deaf-athletes-at-olympic-trials/2012/04/19/gIQAkcbEUT_story.html

- Cloete, Rob (2011, November 1). The Hard of Hearing Hero. The South African. Retrieved 8/12/2016 from http://www.thesouthafrican.com/the-hard-of-hearing-hero/

- (2011, January 21). Olympic swimmer saves boy. Sport24. Retrieved 8/12/2016 from http://www.sport24.co.za/OtherSport/Olympic-swimmer-saves-boy-20110121

- romanSA (2005, April). Celebrating Terence Parkin, a South African sporting hero and icon. SkyScraperCity. Retrieved 8/12/2016 from http://www.skyscrapercity.com/showthread.php?t=986408

- Terence Parkin. Twitter. Retrieved 8/12/2016 from https://twitter.com/TerenceParkin

ADVERTISEMENTS

Marta Belsky is Deaf and a third generation ASL user. She has been teaching ASL for over 35 years and enjoys sharing her native language with new users. She has a Bachelor's degree from Gallaudet University and a Masters in Deaf Education from Western Maryland College. She has taught ASL at multiple universities, coordinated interpreter services at a major university, and is a co-owner of Signing Savvy.

Marta Belsky is Deaf and a third generation ASL user. She has been teaching ASL for over 35 years and enjoys sharing her native language with new users. She has a Bachelor's degree from Gallaudet University and a Masters in Deaf Education from Western Maryland College. She has taught ASL at multiple universities, coordinated interpreter services at a major university, and is a co-owner of Signing Savvy. Living Loud: Heather Whitestone - First Deaf Miss America

Living Loud: Heather Whitestone - First Deaf Miss America Living Loud: Curtis Pride - Major League Baseball Player

Living Loud: Curtis Pride - Major League Baseball Player Living Loud: Juliette Gordon Low - Founder of the Girl Scouts and Philanthropist

Living Loud: Juliette Gordon Low - Founder of the Girl Scouts and Philanthropist