Debbie Wright's Story: A Journey of Discovery with Usher Syndrome and Being Deafblind

While in the company of friends seeking a cure for blindness at a VisionWalk luncheon held by The Foundation Fighting Blindness (FFB), Debbie Wright and her mother Joan candidly share their personal story - their choices, the learning, denying, and accepting the reality of living with Usher syndrome and being Deafblind. This is Debbie Wright's story, as told by Debbie and her mother Joan - a journey of discovery with Usher syndrome and being Deafblind.

An Important Question: Can Debbie Hear?

Debbie Wright as a baby. (Source: Wright Family)

For Debbie Wright, the diagnosis of her hearing loss would take nearly ten months at the persistence only of her mother. Her mother, Joan, was a special education teacher observant and intuitive in working with blind children. Joan clearly remembers the day Debbie was born, her third child, along with the events before being released from the hospital.

It was June 1969. After a normal delivery, the customary hospital stay was three days or more. Debbie was brought in for feeding after delivery; she was lying on the foot of Joan’s hospital bed. Suddenly a food tray crashed to the floor in the hallway, startling everyone, but not Debbie.

Joan was puzzled. Joan shared her concern with Debbie’s dad, Richard. Richard assured her, they had two children at home who could hear just fine, naturally their third child could hear also. Each day in the hospital, Joan kept a watchful eye on Debbie’s responses to sound. Debbie was not underweight and did not present any other reason to suspect that she might have a hearing loss that would warrant medical concern. However, before leaving to take Debbie home she had convinced the doctor to perform a hearing screening.

The audiogram for Debbie was performed in Joan’s hospital room. Joan recalls, "the tools were primitive." The room was noisy with loud banging and the slamming of doors. Nonetheless Debbie’s hospital audiogram recorded "normal" hearing.

Causes of Hearing Loss in Newborns

About 2 to 3 out of every 1,000 children in the United States are born with a detectable level of hearing loss in one or both ears.

More than 90% of deaf children are born to hearing parents. About 1 out of 2 cases of hearing loss in babies is due to genetic causes. Some babies with a genetic cause for their hearing loss might have family members who also have a hearing loss. However, it’s important to note that less than 10% of children born deaf are born to deaf parents.

About 1 out of 3 babies with genetic hearing loss have a “syndrome.” This means they have other conditions in addition to the hearing loss, such as Down syndrome or Usher syndrome. It’s reported that 1 out of 4 cases of hearing loss in babies is due to maternal infections during pregnancy, complications after birth, and head trauma. For about 1 out of 4 babies born with hearing loss, the cause is unknown.

Resources:

- National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD). (2016, December 15). Quick Statistics About Hearing. Retrieved 3/28/2017 from https://www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/statistics/quick-statistics-hearing

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities (NCBDDD). (2015, October 23). Hearing Loss in Children: Causes and Risk Factors. Retrieved 3/28/2017 from https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/hearingloss/facts.html

Joan’s concerns were disregarded at Debbie’s wellness checkups. Each visit the doctor performed his own little hearing test concluding "hearing grows." He would explain Debbie was fine and say maybe the next month they would see nothing is wrong with her hearing, it’s normal.

Finally at three months of age Joan convinced the pediatrician Debbie was not hearing like she should. The doctor sent Debbie to an audiologist. The audiologist evaluation consisted of one primitive test - a demonstration for a group of residents. She shook a rattle while moving it around Debbie’s face. Debbie responded! Joan instantly declared, “I know, she can see!” Leaving the appointment with no more answers than she had before, Joan continued to perceive her child could see, but was not responding appropriately to sound. Joan made more appointments, asked more questions, until the medical professionals heard her.

An extended stay of five days at a local hospital was recommended to investigate and identify Debbie's audio abilities. An audiologist and specialist working with hard of hearing infants prescribed a hearing aid. After more visits a second hearing aid was ordered for Debbie. Her mother’s intuition was right; finally, at ten months of age, Debbie had not one, but two hearing aids. Debbie was born with a congenital hearing loss, meaning the loss occurred before birth, and she was profoundly deaf.

This is an example of an audiogram. An audiogram is a graph that shows results of hearing tests. This example shows the typical hearing level (level of loudness) and frequency (low to high pitch) of different items. With normal hearing, the softest sounds heard are between -10 and 25 dB. If sounds are louder than 25 dB and they still can’t be heard, then there is some degree of hearing loss. The term “Speech Banana” is used to describe the area on the audiogram where phonemes (sounds of human speech) are typically heard. (Sources: Signing Savvy, American Academy of Audiology, and Phonak)

With a profound hearing loss, a child receives very little auditory information. A speech banana provides a clear picture of sounds identifying frequency in hertz and the intensity in decibels. Debbie’s hearing loss at ten months of age was 95 decibels. Amplified sounds heard with hearing aids are not the same as normal hearing. The Wrights wanted Debbie to learn to speak since they all spoke. Debbie’s education began immediately.

Early Hearing Detection and Intervention

Interestingly, it was also the year Debbie was born, in 1969, that the Joint Committee on Infant Hearing was formed by a team of people in audiology, otolaryngology, pediatrics, and nursing to make recommendations for early detection of hearing loss. The importance of identifying congenital hearing loss during the first few months of life has been recognized since the 1940’s. However, it was difficult to implement programs for identifying hearing loss during the first few months of life until effective newborn hearing screening equipment and procedures became available in the late 1980s. The Joint Committee on Infant Hearing is an advocate for Early Hearing Detection and Intervention.

Early Hearing Detection and Intervention refers to the practice of screening every newborn for hearing loss prior to hospital discharge. Infants not passing the screening receive diagnostic evaluation before three months of age and, when necessary, are enrolled in early intervention programs by six months of age. All 50 states and the District of Columbia have Early Hearing Detection and Intervention laws or voluntary compliance programs that screen hearing.

Resources:

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (n.d.). Early Hearing Detection and Intervention (EHDI). Retrieved 3/28/2017 from http://www.asha.org/Advocacy/federal/Early-Hearing-Detection-and-Intervention/

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (2003) History of the Joint Committee on Infant Hearing. Retrieved 3/28/2017 from http://www.asha.org/aud/JCIH-History/

- White, K. R. (2003). The current status of EHDI programs in the United States. Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews, 9, 79–88. Retrieved 3/28/2017 from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/mrdd.10063/abstract

A Mission to Help Debbie to Speak: Immersion into Oral Education

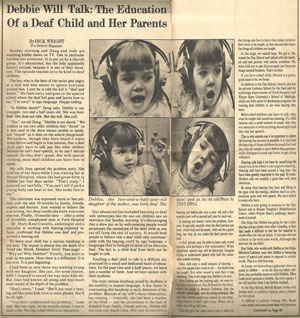

Debbie’s dad penned an article in the Detroit Magazine, "Debbie Will Talk: The Education of a Deaf Child and Her Parents." He wrote, "Since my wife and I and our two older children hear, it is natural that our overriding concern is that Debbie learned to speak, to communicate with the hearing world." The Wrights utilized every source available to achieve their goal to have Debbie speak. They joined the Greater Detroit Association of Oral Education of Hearing Impaired. They looked into the Alexander Graham Bell Association for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing. They sought out the Spencer Tracy Correspondence Course for Lip Reading. They utilized the Detroit Day School for the Deaf, Detroit Medical Rehabilitation Center and programs offered by Wayne State University.

Article: Debbie will talk: The education of a Deaf child and her parents (Source: Scanned article provided from the Wright Family. Citation: Wright, D. (1972, March 12). The Detroit Magazine / The Detroit Free Press.)

Debbie Wright as a child. (Source: Wright Family)

Debbie was immersed into an oral program at home and once a week Debbie, at ten months of age, attended an auditory training program. With Joan’s professional training as a special education teacher, she knew, "Debbie was not dumb; she just had a problem hearing." Joan labeled everything in the house for Debbie. The furniture, doors, lights, toys, anything and everything was tagged with written words. At eighteen months old, Debbie attended a weekly oral program at both the Detroit Day School for the Deaf and Detroit Medical Rehabilitation Center.

With great joy, Joan told about the day her toddler responded to the word "BALL." Joan had said, “Debbie, go get your ball.” For the first time Debbie understood the motion or movement of a person’s mouth, their facial expression and body language all had meaning. Joan was pleased that Debbie was walking by age two. By age three Debbie attended all-day preschool. She did not learn any sign language in preschool. Joan remarked, "Some of the older kids signed a little. It was an oral program where Debbie was being taught to speak."

Debbie Wright as a kid. (Source: Wright Family)

Debbie and her family broke ground for special education in the mainstream program and full-day kindergarten. Debbie was mainstreamed before a structure for mainstreamed education was understood. Joan recalls Debbie’s kindergarten IQ tested at 145, she was a very bright child. Debbie attended Detroit Day School for the Deaf for morning kindergarten classes in an oral program. In the afternoon she went to a regular kindergarten classroom in the public Grosse Pointe Schools. There Debbie was included in class with the hearing world (this practice, when children with special needs are educated in regular classrooms, is called mainstreaming).

The U.S. Department of Education began to realize a shift in education for special needs children. Half-day kindergarten was the model of education until recent years, then full-day kindergarten had become the new standard. The Education for All Handicapped Children Act of 1975 passed when Debbie was six years old. Over the years more acts were passed to improve the education provided for children classified as handicapped. Today IDEA, Individuals with Disabilities Education Act 2004, is in place in our public school system.

It’s important to note members of the Deaf community do not consider deafness a handicap or disability. A study entitled Deafness as Culture explained, "On the one hand, deafness has historically been viewed as a physical impairment associated with such disabilities as blindness, cognitive, and motor impairments. On the other hand, views on deafness as a culture have recently emerged that consider deafness as a trait, not as a disability" (Jones, M. A. (2002, Spring). Deafness as Culture: A Psychosocial Perspective. Disability Studies Quarterly, 22(2), 51-60. Retrieved 5/30/2017 from http://dsq-sds.org/article/view/344/435).

Special Education Laws

Public Law 94-142: The Education for All Handicapped Children Act (EHA) of 1975

Public Law 94-142, also known as The Education for All Handicapped Children Act of 1975, was passed November 19, 1975. “P.L. 94-142 guaranteed a free appropriate public education to each child with a disability. This law had a dramatic, positive impact on millions of children with disabilities in every state and each local community across the country.” Congress amended and renamed this law several times after it was enacted.

Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA)

Congress renamed The Education for All Handicapped Children Act (P.L. 94-142) in 1990 to The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). “The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) is a law ensuring services to children with disabilities throughout the nation. IDEA governs how states and public agencies provide early intervention, special education and related services to more than 6.5 million eligible infants, toddlers, children and youth with disabilities. Infants and toddlers with disabilities (birth-2) and their families receive early intervention services under IDEA Part C. Children and youth (ages 3-21) receive special education and related services under IDEA Part B.”

Resources:

- U.S. Department of Education. (2010). Thirty-five Years of Progress in Educating Children With Disabilities Through IDEA. Washington, D.C.: Office of Special Education and Rehabilitative Services. Retrieved 5/10/2017 from https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/osers/idea35/history/idea-35-history.pdf

- U.S. Department of Education. (n.d.). Building the Legacy: IDEA 2004. Retrieved 5/10/2017 from http://idea.ed.gov

Children and youth who are profoundly deaf are eligible for programs and services mandated by IDEA. In the process each child has a written plan to meet their educational needs. The written plan is their Individualized Education Program (IEP). Together a team discusses the best practices for each student; an IEP is drafted to satisfy their special needs to an equal education. There is tremendous debate over the programs and services that best serve Deaf children in the mainstream school system. The Wrights agreed on an oral program for Debbie who was about to face even a greater challenge, losing her vision.

A Diagnosis: Confirmed Usher Syndrome

The nerve cell damage that caused Debbie's profound hearing loss was only half of her worries. At age seven Debbie's parents learned she also had RP or retinitis pigmentosa. Joan and Richard were devastated and determined it wise to spare Debbie the anxiety of knowing she would become blind until she was fourteen years of age. Even after telling Debbie she, "would be losing eye sight," it did not fully sink in until she was in her late twenties.

It was at a VisionWalk Kick‐off luncheon that I interviewed Debbie Wright. She had a favorite interpreter with her. Debbie requested the interpreter voice for her and sign for me; I was a student learning sign language at the time. The three of us sat in a little circle that put both the interpreter and me in Debbie’s narrow window of sight. Throughout the interview Debbie kept her focus on communicating with me as her interpreter voiced the communication.

Debbie described the first time she realized she was really becoming blind. She began with a deep breath and a slight cringe, "I had been at the mall, I ran straight into a lady!" Using classifiers while signing, Debbie illustrated casually strolling through the mall, enjoying the day, minding her own business, when suddenly she was face to face with a woman.

The interpreter relays Debbie’s story, "I walked straight into her, I never saw her. The woman was shorter than me. Before I realized she was there, I walked smack into her, and nearly knocked her down."

Leaning back, slightly pausing, she closed her eyes but for a moment. No interpreter was needed to understand the communication, "I felt so bad."

Debbie had come face to face with the brutality of Usher’s syndrome, "I went home and cried."

Then without hesitation or further remorse she affirmed, "I accepted that I was going blind. I started using a white cane."

Compassion let a tear well up and in the next breath admiration for her bravery, her strength of character to accept a cane. Two of her five senses were damaged by a recessive inheritance pattern; Usher syndrome was running her life and Debbie had no voice in the matter. Debbie did have a choice to not give up, count her blessings, and move forward.

About Usher Syndrome

One third of genetically based hearing losses are syndromic, which are associated with abnormalities. The combination of progressive vision loss and hearing impairment are known as Usher syndrome according to The Foundation Fighting Blindness:

“Usher syndrome is passed from parents to their offspring through an autosomal recessive inheritance pattern. In this type of inheritance, two copies of a mutated gene, one from each parent, are required for the child to be affected. A person with only one copy of the gene is a carrier and rarely has any symptoms.”

The Problem with Nerve Cells and Photoreceptor Cells

According to The Foundation Fighting Blindness, the mutation expresses in the nerve cells of the cochlea, which is responsible for sound in the inner ear. The damaged nerve cells cause sound to never reach the auditory nerve and send the audio message to the brain. Children may be born completely deaf, have moderate to severe hearing impairment or be born with good or mild hearing impairment, depending if the infant has Usher syndrome type 1, type 2 or type 3.

The photoreceptor cells or the rods and cones, in the back of the eye, are responsible for converting light into electrical impulses. These electrical impulses then transport the visual message to the brain. Retinitis pigmentosa is generally not realized until adolescence or early adulthood. The first symptoms of RP are night blindness and peripheral vision loss. As the rods and cones degenerate the visual field becomes progressively smaller. There are many genetic variations responsible for nerve cells and photoreceptor cells to malfunction. This and much more information can be found at www.blindness.org.

Resources:

- Foundation Fighting Blindness. (n.d.). Usher Syndrome. Retrieved 5/10/2017 from http://www.blindness.org/usher-syndrome

- Foundation Fighting Blindness. (n.d.). Retinitis Pigmentosa. Retrieved 5/10/2017 from http://www.blindness.org/retinitis-pigmentosa

A Reason to Celebrate: Educational Achievements

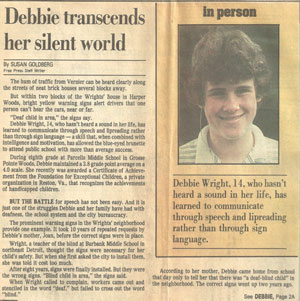

Achievement! Debbie’s educational experience was never lacking of ample success. She achieved high grades while in Parcells Middle School in Grosse Pointe Woods. Debbie earned a 3.8 grade point average. At age 14, Debbie was awarded a Certificate of Achievement from the Council for Exceptional Children, from Reston, Virginia. Joan saved the article from the Free Press, “Debbie transcends her silent world” celebrating her achievements and the award that was presented to her by her school.

Article: Debbie transcends her silent world (Source: Scanned article provided from the Wright Family. Citation: Goldberg, S. (1983, July 7). Debbie transcends her silent world. The Detroit Free Press.)

Attending Grosse Pointe North High School, Debbie won a Detroit Free Press writing contest and the nickname, “Kid with the Wright stuff.” While her sense of sight and sound were limited, Debbie had an amazing sense of humor joking, “I have both senses of humor, blind and deaf.”

Article: Kid with the Wright stuff earns Wayne State bachelor's degree (Source: Scanned article provided from the Wright Family. Citation: (1993, January 14). Kid with the Wright stuff earns Wayne State bachelor's degree. Inside Wayne State.)

After high school, Debbie attended Madonna University where she quickly learned sign language. Joan remembers she practiced non‐stop. Signing everything and anything entering her senses, including closed-captioned television. Debbie had found the power of a spatial-visual language to gain information quickly and effortlessly. Joan said early in Debbie’s life that she was a very bright girl, "she just couldn’t hear like we do." Madonna University’s program for Sign Language Studies is structured for students to gain fluency while earning a bachelor’s degree. In two years, she had learned ASL. Debbie quickly became a fluent signer.

The quest for knowledge continued, taking Debbie to the Helen Keller National Center for Deaf-Blind in a program for youth and adults. This was a new experience for Debbie, being away from home. She was twenty years old. Classes began in June and by November Debbie was ready to come home to be near family.

Debbie ventured out again to Hofstra University in Hempstead, New York. Here she was again in a mainstream environment and the only Deaf student. This time though, Debbie had a new language that she loved, but no one to communicate in ASL with her.

Article: Kid with the Wright stuff earns Wayne State bachelor's degree (Source: Scanned article provided from the Wright Family. Citation: (1993, January 14). Kid with the Wright stuff earns Wayne State bachelor's degree. Inside Wayne State.)

Eventually, Debbie followed the rest of her family in attending Wayne State University - where her father had become a Professor and the Program Director for the Journalism Department. Then fluent in ASL, Debbie was pleased that the office of Wayne State Handicapper Educational Services provided her with interpreters. Debbie and Joan confirmed that finding qualified interpreters in the early 90’s was difficult. Wayne State continued to provide interpreters, seeking ones who were qualified and the best match for Debbie. The “kid with the Wright stuff” earned a bachelor’s degree in Psychology. In an article in the Inside Wayne State paper the students, staff, and professors had all come to know Debbie and admire her positive outlook. She affirmed, “Don't grieve for what you’ve lost, rather appreciate what you have and who you are, how you are.”

“Don't grieve for what you’ve lost, rather appreciate what you have and who you are, how you are.”

- Debbie Wright

Debbie’s family congratulated and celebrated with Debbie every step along her journey. Attaining a Masters Degree in Rehab Counseling from Wayne State University gave her an advantage. Her family was especially proud that after graduation Jewish Vocational Services hired her as a caseworker.

A Curve Ball: Life’s Challenges

The Cochlear implant (CI), a surgically implanted electronic device to simulate hearing, sometimes fails! At forty-one Debbie got a CI. Joan was a big advocate for Debbie to get the Cochlear implant, hoping it would help her to communicate with the family.

While Joan has taken sign language classes, sign language has not come as easily for her or the family as it did for Debbie. Joan genuinely wanted her daughter to hear her voice, talk to her and with her; that was her expectation for the CI.

In anticipation of Debbie hearing, Joan offered, "We work with the Cochlear implant to learn environmental sounds, but the Cochlear implant is not giving her speech sounds. Debbie needed the Cochlear implant at age two, but it was not available to us then."

Debbie shared, "At forty-one I got a Cochlear implant. It was not successful." She affirmed as a matter of fact, "It should have allowed me to at least tell the difference between a dog barking or a car going down the road. But I can’t hear."

Describing the sensations of her Cochlear implant Debbie shared, "I feel vibrations through my eyes, but it was a failure. I wish I had not had the surgery. I am not wearing it now."

To Debbie the CI was like one of the numerous hearing aids her mom wanted her to wear, "She had me wear so many different hearing aids over the years." Debbie simply preferred not to wear hearing devices of any kind, ever.

There are numerous factors to consider when contemplating a Cochlear implant. As Debbie and Joan learned, they do not always work. The problem of a CI that is ineffective, is not the only concern for individuals who have an electronic Cochlear implant.

Since our interview Debbie experienced a medical situation that required her to have an MRI. A patient implanted with a Cochlear implant cannot undergo an MRI. In order for Debbie to have the needed MRI she had to first undergo surgery to have the implant removed. After the CI was removed Debbie could have the needed MRI. Then another surgery was required to replace the CI. At a later date, Debbie had a fourth surgery to permanently remove her Cochlear implant. All residual hearing is destroyed when a CI is removed. Debbie’s communication is gathered in silence without a sound, sensitive to vibrations, feeling the movement around her she absorbs information through diminishing sight, is there a chance Debbie’s vision can be restored?

An On-Going Discovery: Finding Help and Hope

At a VisionWalk for The Foundation Fighting Blindness (Sources: Sara Develbiss, Foundation Fighting Blindness; Kathleen Marcath).

The search for a cure for retinal degenerative eye diseases began before Debbie or her family knew she would ever benefit from a cure. It was 1971 when Gordon Gund established The Foundation Fighting Blindness (FFB). The Eastern Michigan Chapter had been established and in 1991 Joan became the chapter President. Joan emphatically praises FFB for recognizing the problem, offering hope and pressing in to find a cure for retinal degenerative eye diseases. The foundation provides valuable information on eye diseases, research updates, low vision resources, and networking opportunities. Through local chapters and national conferences FFB members stay informed, connected, and actively living a full life, rich with purpose.

Joan along with millions of parents, children, family members and friends participate each year raising funds, keeping an eye on the cure. Over the years the foundation evolved and created VisionWalk. VisionWalks are held throughout the United States to raise awareness and funds for critical research.

Debbie’s Perspective

The VisionWalk luncheon was complete as guests shared stories and began parting, but I had a few more questions for Debbie. When asked further about her thoughts she was clear, "Yes, I hope FFB with VisionWalk will find a cure. I believe they will do that in my lifetime. That is very exciting!"

Debbie responded about her desire to see, "Absolutely! But I am fortunate that my vision has stayed the same for about thirteen‐fourteen years now. That is a very good thing."

Her response was a little different when asked if she wished she could hear.

Affirmatively she signed as the interpreter reiterated her message, "No, if I were born black would I want to have surgery to change my skin color? Do something to change me into another color? No!"

After a slight pause with deep conviction and a passionate manner she continued, "That is ridiculous, that would not be who I am. I am Deaf. That is who I am, and I do not, and would not, want to change that."

Having fully expressed her position on who she is, she glanced at the guide dog resting on the floor next to her and reached down, petting him with a smile, "I have my guide dog, Pete."

Pausing a moment she continued, "The biggest frustration in my life is communication, obviously with hearing people."

Debbie set up the interview in such a way that her "voice" through the interpreter would be heard clearly and directed to the person she was in communication with, that being me. Through this interview I realized the brilliance Debbie possesses. In setting up everyone’s role and position in the interview she had subtly made the point to include all parties in the conversation, leaving no one out, as so often happens to Deaf people in a hearing world.

As I paused to reflect, Debbie continued signing and the interpreter voiced, "I think I had a great education in the Grosse Pointe School System. I would not want to change that. I would not have liked going to a residential school."

Debbie concluded, "I do wish I had learned sign language when I was younger."

I thanked Debbie for so candidly sharing the personal details of her life feeling very humbled by the experience and thankful for the opportunity to share who Debbie Wright is.

Joan’s Perspective

I asked about looking back, would you change anything? Joan replied, "I never would have considered sending Debbie to MSD (Michigan School for the Deaf in Flint). She needs to be in a hearing world, we are all hearing."

She quickly added, "Do over? I would go to Madonna to learn sign language earlier in life, now I have arthritis and I’m slow."

With all life challenges surmised for Debbie, Joan’s concern for her daughter is felt in saying, "Debbie fits in with the Deaf community, but she does not drive, transportation is an issue."

Clarifying the reason for permanently removing the CI, "We decided to have the CI removed because Debbie was not getting sounds in her ear--only vibrations in her eye."

Joining the FFB and serving as Michigan Chapter President, Joan’s family worked together for a worthy cause. They met lifelong friends, engaged with a community of passionate people with a common goal. Like Debbie, Joan is very hopeful that restoration of vision is coming soon. That would be the tremendous blessing for Debbie.

A Happy Life: Life is a Choice, New Every Day

Debbie with her mother Joan. (Source: Wright Family)

Currently, Debbie serves on the board for Deaf C.A.N. Debbie’s guide dog Pete died a couple years back. Sophie has stepped in as Debbie’s new guide dog, a faithful and constant companion, absolutely a source of joy. She continues to work at Ascension Medical Center - St. John Providence in the medical education department. Sophie joins Debbie on the bus going to work, going wherever she goes. Debbie hears without sound through a small window of vision, the motions and vibrations of life are gathered providing information about the world around her. Joan and Debbie communicate well together as loving moms and daughters do. Joan continues to offer and provide encouragement and support for her daughter.

Thank you so much Debbie for being true to yourself, and for your profound attitude of appreciation for what you do have. Thank you for inspiring the world with your unquenchable thirst for learning and tenaciously pressing in to achieve all that you have. I want to thank you for being open and candid, affording me the privilege to share your story with all people who are Deaf and blind and hearing. An old adage says, it takes a village to raise a child. Together with your mom, the village has learned it takes perseverance and a love for life that never gives up to carry on in spite of the challenge of Usher syndrome and being Deafblind.

Joan began the conversation mom-to-mom telling me about her affiliation with The Foundation Fighting Blindness (FFB) and her hope for her daughter to see, to hear, to communicate. I greatly admire and respect Joan for who she is as a mother who loves her daughter to the moon and back. Thank you Joan for sharing your journey, the trials, the disappointments and the torch of hope you carry to light the way to a brighter future for sons and daughters, for families and the future free from deafness and blindness.

Debbie and Joan are passionate about The Foundation Fighting Blindness (FFB) and encourage anyone interested in being an advocate for the Deafblind to participate in a VisionWalk or support the The Foundation Fighting Blindness (FFB). They are hopeful that a cure for blindness is in sight.

ADVERTISEMENTS

Kathleen Marcath has a BA in Deaf Community Studies and is passionate about helping students and families make connections through American Sign Language. Kathleen has the privilege to work with hard of hearing students providing sign language support, building vocabulary, confidence and community. She strives to create an atmosphere that promotes harmony, excellence, exploration and certainly fun. In establishing ASL Educational Services – Making Connections she is helping people tap into their potential and and the hidden potential of American Sign Language. Currently, Kathleen serves as President for the Michigan Chapter of the Foundation Fighting Blindness. If you are interested in creating new possibilities for yourself, your family or your school, Kathleen can be contacted at

Kathleen Marcath has a BA in Deaf Community Studies and is passionate about helping students and families make connections through American Sign Language. Kathleen has the privilege to work with hard of hearing students providing sign language support, building vocabulary, confidence and community. She strives to create an atmosphere that promotes harmony, excellence, exploration and certainly fun. In establishing ASL Educational Services – Making Connections she is helping people tap into their potential and and the hidden potential of American Sign Language. Currently, Kathleen serves as President for the Michigan Chapter of the Foundation Fighting Blindness. If you are interested in creating new possibilities for yourself, your family or your school, Kathleen can be contacted at  Living Loud: Terence Parkin - Olympic Swimmer

Living Loud: Terence Parkin - Olympic Swimmer Practice American Sign Language (ASL) With an ASL Expert Through Video Chat

Practice American Sign Language (ASL) With an ASL Expert Through Video Chat The Importance of Early Exposure to American Sign Language with Deaf Children

The Importance of Early Exposure to American Sign Language with Deaf Children