The Importance of Early Exposure to American Sign Language with Deaf Children

Around 8,000 children are born deaf or hard of hearing each year in the United States.1 95% of those children are born into hearing families.18 This means a few things – the majority of hard of hearing children are born into families that do not use sign language and their parents do not have previous experience with raising and educating a deaf child. The options and information may be overwhelming for parents, but just like raising any child, each child and family is different and there isn’t a “one size fits all” plan to execute. Luckily there is research to help serve as a guide.

The Gift of Language

The greatest gift you can give to a child is language. Children need language.1, 27 Babies are capable of learning any language, and multiple languages, from birth.6, 13

The key is early exposure and full access to a natural language.10 A natural language is a language that has developed naturally through use and includes all of the linguistic levels – phonology, morphology, lexicon, syntax, and discourse. English and American Sign Language (ASL) are both full, natural languages.

Our brains are built to process language the same, whether it is signed or spoken.1, 22 So it doesn’t matter if a child has access to early spoken language or early sign language, it matters more that they have full access to language (the ability to receive communication input). For some children, this will mean English, for some this will mean American Sign Language, and for others it may mean both.

Taking Advantage of the “Critical Period”

Some researchers believe a “critical period” exists for language acquisition. The hypothesis is that during this period, it is much easier to learn languages and if exposure to language begins after this period, then it may be impossible to become fluent in that language. At birth, babies have the ability to learn any language, but around 8-10 months, they lose their ability to discriminate sounds in other languages (sounds not relevant to the baby’s own language).13, 14 The critical period extends through infancy and different researchers believe this critical period ends at different points between 5 years old and puberty.15 Many professionals who work with deaf children assume that there is a critical period for spoken language, but not sign language, but research shows that is simply not true.8 The critical period extends to all language learning, including sign language.

There are many advantages to early language learning.

- Early first language acquisition contributes to native-like fluency as an adult.16

- Early first language acquisition supports more effective second language learning. 16

On the other hand, there are several negative effects to late language exposure.

- A lack of early first language acquisition impairs the ability to learn language throughout life and decreases language proficiency for any language in adulthood. 16

- Late exposure to language effects linguistic processing and cognitive development.19

- Late language development can delay cognitive reasoning, such as the Theory of Mind, which allows children to distinguish between what they know and what others know, to understand others may think differently than themselves, and to have the ability to guess other’s actions.20, 34

- If input is delayed by as little as 4-6 years, long-lasting effects can be observed in language production, comprehension, and processing.21

There are several reasons why early exposure is critical to language acquisition. Children simply have more time to learn language when they are exposed earlier in life, and have a less stressful learning environment with less distractions where they can practice.

- Babies benefit from learning language through “motherese,” when learning either sign or speech. Motherese, also called child-directed signing or speech (CDS), is modified speaking or signing directed for the baby. In speech, motherese includes using a higher pitch and exaggerated stress and intonation patterns. When signing or speaking, motherese includes shorter statements, frequent repetitions, and frequent directives.19

- Another important aspect of motherese in signing is the use of eye gaze and joint attention to make sure the baby understands what you are talking about (by looking at the subject) and that you are in their line of sight and they can see you when you are signing. These techniques help children learn language and also important attention and turn-based lessons. When children are in school, the classroom can be a distracting environment and a teacher or interpreter is often signing to many children and cannot provide one-on-one attention to help with language acquisition.19

- Babies are able to “practice” language in the form of babbling. At first English babbling is just playing with making sounds and over time those sounds become more English-like and eventually they begin to say their first words. ASL babbling lets babies practice playing with handshapes, location, and movement until they begin to produce their first signs.19

- Babies have the time to leisurely learn language before having additional pressures, such as needing to produce language on demand, or the expectation that they are learning new content and curriculum, not just language acquisition.19

The important take away to learn from the “critical period” hypothesis, is that early access to language is important. However, other researchers prefer to call this period the “optimal period” or “sensitive period”8 because, although perhaps less efficiently, language learning still occurs after this period.16 If you have already missed this period, you should not be discouraged to start language acquisition. Late detection of hearing loss is one of the biggest barriers to early language acquisition. Late language exposed signers can still become strong signers with great signing skills. Where researchers find the biggest difference between early and late learners is when they are under stress, like when they have to recall information quickly and when taking a test. Now is always a good time to start learning language.

Advantages of Sign Language Use

Babies and young children don’t learn language by simply copying adults, explicit instruction, or training. They learn language by building a system of grammar based on the input they receive, which is why it is critical they have full access to communication input.

In order to have full access to a language, the child must have the ability to receive the communication input. Since children who are hard of hearing have trouble hearing spoken language, they are often not able to fully access it as a communication input. American Sign Language is the language of the deaf and is a fully accessible language that does not require hearing for input.

Babies are born interested in and looking for language, and not just speech, but spoken or signed language. This indicates babies are equally interested and able to learn either spoken or signed language. They are able to detect patterns in visual language, even with no previous language exposure. They also seem to recognize the same kind of structured patterns found in spoken language in ASL and prefer ASL (a full, natural language) over non-linguistic pantomime gesturing.13

Research has found many advantages to learning sign language, including:

- Early first language learning helps facilitate, and may even be necessary, for learning a second language later in life.19

- Early exposed signers have better academic performance compared to late exposed deaf in a variety of areas,33 including better performance on:

- tests of English syntax25, 33

- reading tasks5, 32

- written language tasks31

- vocabulary26

- overall academic achievement17, 29

- Even moderate fluency in ASL benefits English literacy for Deaf children.30

- Kids who understand more sign language, understand more English.35

- Kids who produce more sign language, produce more English.35

- Strong adult signers have better ASL narrative comprehension, and also higher English reading scores.7

- The experience of “speaking” two languages (like ASL and English) on a regular basis has broad implications for cognitive ability, enhancing executive control functions and protecting the brain across the life span.2, 9, 11

- Bilingualism may protect against age-related cognitive decline.4 With all else being equal, one study found the age of dementia onset for bilinguals was 4 years later than it was for monolinguals.3

Common Concerns – As hearing parents, we don’t know ASL well.

Some hearing parents may be concerned their own signing skills are not good enough to model as a communication input for their children. Learning ASL and using it with your child is a great way to communicate with them, increase bonding, and help them learn ASL, but there are several factors involved.

- The deaf students who perform best academically usually are the ones whose parents have effectively communicated with them from an early age.12

- It was found children are able to surpass the level of their input - so parents’ ASL may be grammatically inconsistent, but the child is still able to regularize inconsistent input and produce ASL that is more native-like than their parents’ signing.28

- Children are shaped by more than just their parents. The culture and peer groups children are exposed to play an important role.24 So finding playgroups or preschools where they can interact with other hard of hearing peers is helpful.

- Being exposed to a diverse set of signers, of different ages and abilities, is also helpful. Anyone from siblings, extended family members, friends, peers, and community members help shape the child’s learning environment and language acquisition, and help them to practice both receptive and expressive signing skills.

Common Concerns – Is it too difficult for young children to learn two languages (English and ASL) at once? Maybe we should just focus on one language to start.

There is a misconceived fear that teaching babies more than one language too early may cause language delays or language confusion or that the child may never be as competent in either of the languages as a monolingual child is in one. In fact, research shows babies know that they are acquiring two distinct languages and are able to learn them without language delay or language confusion. Bilingual babies are able to reach the classic language milestones on a similar timetable as monolingual babies, such as when they say their first word, when they can say their first fifty words, and when they say their first two-word combinations. There are a few differences though. For example, when counting the child’s first fifty words, the tally would come from a total of words produced in both languages. Young children may also show a language preference and use one of their languages more, however, this is not a delay in language learning, it simply shows a preference, which could change over time, and is often related to the child’s primary sociolinguistic group (for example, the language used by peer groups in school, or if one parent is home all day using one language with a baby, it will often be preferred over a second language that is used when the rest of the family is home only at night). It doesn’t make sense to take away any language to focus on just one. Early exposure of both languages is what is best for the child and will help the child to reach fullest mastery in each of the languages.23

Conclusion

The key to learning language and becoming fluent is early exposure and full access to a natural language.10 Babies are capable of learning any language, and multiple languages, from birth.6, 13 Research shows there are many benefits to learning ASL, and the sooner you can start, the better. There are both linguistic and cognitive advantages to being bilingual. Learning both ASL and English from an early age will help the child to reach fluency in both languages. The best time to start learning language is now.

Sources:

- Bavelier, D., Newport, E.L., & Supalla, T. (2003, January 01). Children Need Natural Languages, Signed or Spoken. The Dana Foundation. Retrieved from http://www.dana.org/Cerebrum/Default.aspx?id=39306

- Bialystok, E., & Craik, F.I.M. (2010). Cognitive and Linguistic Processing in the Bilingual Mind. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 19(1), 19-23.

- Bialystok, E., Craik, F.I.M., & Freedman, M. (2007). Bilingualism as a protection against the onset of symptoms of dementia. Neuropsychologia, 45, 459-464.

- Bialystok, E., Craik, F.I.M., Klein, R., & Viswanathan, M. (2004). Bilingualism, aging, and cognitive control: Evidence from the Simon task. Psychology and Aging, 19, 290-303.

- Brasel, K. & Quigley, S. (1977, March). Influence of Certain Language and Communication Environments in Early Childhood on the Development of Language in Deaf Individuals. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 20, 95-107.

- Brentari, D. (Ed.). (2010). Sign languages. Cambridge University Press.

- Chamberlain, C., & Mayberry, R. (2008, July 1). American Sign Language syntactic and narrative comprehension in skilled and less skilled readers: Bilingual and bimodal evidence for the linguistic basis of reading. Applied Psycholinguistics, 29(3), 367-388.

- Chen Pichler, D. (2016, Fall). Why sign with deaf babies? [Video Lecture]. Gallaudet University: PST 375 Language Learning by Eye or by Ear.

- Chen Pichler, D. (2016, Fall). Bilingualism: Unimodal and Bimodal [Video Lecture]. Gallaudet University: PST 375 Language Learning by Eye or by Ear.

- Davidson, L.S., Geers, A.E., & Nicholas, J.G. (2014, July). The effects of audibility and novel word learning ability on vocabulary level in children with cochlear implants. Cochlear Implants Int., 15(4), 211-221.

- De Houwer, A. (2009). An introduction to bilingual development. Tonawanda, New York: Multilingual Matters.

- Deaf Education: A new philosophy. Research findings at NTID. Retrieved 10-10-2016 from https://www.rit.edu/showcase/index.php?id=86

- Krentz, U.C., & Corina, D.P. (2008, January). Preference for language in early infancy: the human language bias is not speech specific. Developmental Science, 11(1), 1-9.

- Kuhl, P. (2010, October). Patricia Kuhl: The linguistic genius of babies [Video file]. TED. Retrieved from http://www.ted.com/talks/patricia_kuhl_the_linguistic_genius_of_babies

- Lenneberg, E.H. (1967). Biological Foundations of Language. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Mayberry, R.I. (2010). Early language acquisition and adult language ability: What sign language reveals about the critical period for language. In Marschark, M. & P.E. Spencer (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Deaf Studies, Language, and Education Volume 2 (pp. 281-291). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Meadow, K. (1966). The effects of early manual communication and family climate on the deaf child’s early development. Doctoral dissertation, University of California, Berkeley.

- Mitchell, R.E., & Karchmer, M.A. (2004, Winter). Chasing the Mythical Ten Percent: Parental Hearing Status of Deaf and Hard of Hearing Students in the United States. Sign Language Studies, 4(2), 138-163.

- Morford, J.P., & Mayberry, R.I. (2000). A reexamination of “Early Exposure” and its implications for language acquisition by eye. In Chamberlain, C., Morford, J.P., & R.I. Mayberry (Eds.), Language acquisition by eye (pp. 110-127). New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers.

- Morgan, G. & Kegl, J. (2006, August). Nicaraguan Sign Language and Theory of Mind: the issue of critical periods and abilities. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 47(8), 811-819.

- Newport, E. L., & Supalla, T. (1980). The structuring of language: Clues from the acquisition of signed and spoken language. Signed and spoken language: Biological constraints on linguistic form. Weinheim/Deerfield Beach, FL/Basel: Dahlem Konferenzen. Verlag Chemie.

- Orfanidou, E., Adam, R., Morgan, G., & McQueen, J. M. (2010). Recognition of signed and spoken language: Different sensory inputs, the same segmentation procedure. Journal of Memory and Language, 62(3), 272-283.

- Petitto, L. A., & Holowka, S. (2002). Evaluating attributions of delay and confusion in young bilinguals: Special insights from infants acquiring a signed and a spoken language. Sign Language Studies, 3(1), 4-33.

- Pinker, S. (2003, February). Steven Pinker: Human Nature and the blank slate [Video file]. TED. Retrieved from http://www.ted.com/talks/steven_pinker_chalks_it_up_to_the_blank_slate

- Quigley, S. P., Montanelli, D. S., & Wilbur, R. B. (1976). Some aspects of the verb system in the language of deaf students. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 19 (3), 536-550.

- Quigley, S. P., & Frisina, D. R. (1961). Institutionalization and psycho-educational development of deaf children. Council for Exceptional Children.

- Schick, B., de Villiers, J., de Villiers, P., & Hoffmeister, B. (2002). Theory of mind: Language and cognition in deaf children. The ASHA Leader, 22, 6-7.

- Singleton, J. L., & Newport, E. L. (2004). When learners surpass their models: The acquisition of American Sign Language from inconsistent input. Cognitive psychology, 49(4), 370-407.

- Stevenson, E. (1964). A study of the educational achievement of deaf children of deaf parents. California News, 80(14.3).

- Strong, M., & Prinz, P. M. (1997). A study of the relationship between American Sign Language and English literacy. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 2(1), 37-46.

- Stuckless, E. R., & Birch, J. W. (1966). The influence of early manual communication on the linguistic development of deaf children: I. American Annals of the Deaf.

- Vernon, M., & Koh, S. (1970). Early manual communication and deaf children's achievement. American Annals of the Deaf, 115(5), 527-36.

- Wilbur, R. B. (2000). The use of ASL to support the development of English and literacy. Journal of deaf studies and deaf education, 5(1), 81-104.

- Woolfe, T., Want, S. C., & Siegal, M. (2002). Signposts to development: Theory of mind in deaf children. Child development, 73(3), 768-778.

- Woolfe, T., Herman, R., Roy, P., & Woll, B. (2010). Early vocabulary development in deaf native signers: A British Sign Language adaptation of the communicative development inventories. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 51(3), 322-331.

Signs That Are Close... But Not the Same - Set 1

Signs That Are Close... But Not the Same - Set 1 Tips for Reading with Deaf and Hard of Hearing Children

Tips for Reading with Deaf and Hard of Hearing Children Use Sign Language to Communicate With Your Hearing Baby Before They Can Talk – An Overview of Why to Use American Sign Language (ASL)

Use Sign Language to Communicate With Your Hearing Baby Before They Can Talk – An Overview of Why to Use American Sign Language (ASL) 5 Tips for Creating a Language Rich Environment for Deaf Children Through Routines and Consistency

5 Tips for Creating a Language Rich Environment for Deaf Children Through Routines and Consistency The Meaning Behind Champion Nyle Dimarco’s Freestyle Dance on the Dancing with the Stars Finale

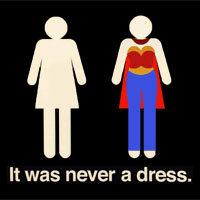

The Meaning Behind Champion Nyle Dimarco’s Freestyle Dance on the Dancing with the Stars Finale Avoiding Stereotypes with Gender when Teaching Sign Language

Avoiding Stereotypes with Gender when Teaching Sign Language

Savvy User EllenFriday, November 4, 2016

I could not possibly agree more. I worked as an educational interpreter for many years. I have been, since my retiredment in 2010, working as a freelance interpreter for adults only.

I have seen so many examples of clients that came up through an oral program or one that only used SEE and struggle with Sign Language now.

My heart breaks when I see the skills they DON'T have and know that for many, it's too late.

Deaf children need THEIR language as soon as possible. When they have a base they can move onto English with a much better understanding of that language - their second.